(note: This is text of a speech given by Kay Gaston on April 28, 2017, relative to the 5 acres closest to the intersection of Anderson Pike and Taft Highway.)

by Kay Baker Gaston

Emma Bell was only ten when she and her parents, B.F. and Martha Ann Mirick Bell, set off from Evansville, Indiana to Walden’s Ridge in June of 1890. Her parents drove a wagon and she rode on her pony. They came up the Sequatchie Valley side of the mountain on the Anderson Pike, passing through the Horseshoe and the settlement at Fairmount Spring before emerging at Albion View on the eastern brow. They reached Chattanooga on July 16th, settling at Red Bank before returning to Walden’s Ridge in the early summer of 1891 to build a frame Victorian house on land B. F. Bell had purchased from the Reverend Joseph T. Woodhead. While the house was under construction they stayed at “Shingle Shanty,” a four room log house partially sided and roofed with white oak shingles, located near a big spring on Frank Woodhead’s property. Just up Anderson Pike was the Oakwood School, where Mrs. Bell began teaching.

Emma made friends with Rose and Minta Stroop, whose family spent summers in their house on the road to Signal Point (now James Boulevard). The girls walked to the post office where there was also a store and a dance pavilion looking out over the old corduroy road replaced by the “W” Road in 1893. They played on the rocks at the Nelson spring and the natural stone bridge at Rocky Dell.

Emma made friends with Rose and Minta Stroop, whose family spent summers in their house on the road to Signal Point (now James Boulevard). The girls walked to the post office where there was also a store and a dance pavilion looking out over the old corduroy road replaced by the “W” Road in 1893. They played on the rocks at the Nelson spring and the natural stone bridge at Rocky Dell.

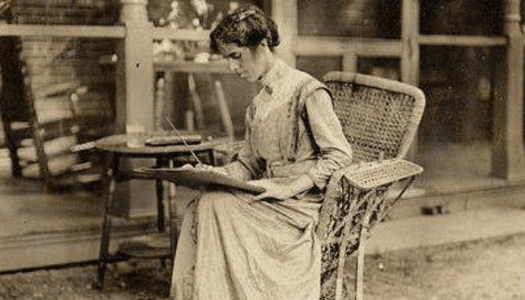

She and Grace Catlow, whose family lived on the old Red Road leading from Albion View to the Signal Point Road, explored on horseback, riding astride and scandalizing the natives. By the time she was 15, Emma virtually lived in the woods. She drew, read, wrote a little, and began associating with the mountain people. In the summer of 1898, when Emma was 18, she met Frank Miles, a handsome mountain youth who drove the hack to and from Chattanooga on the “W” Road. While attending the St. Louis School of Art in 1899 and 1900, Emma corresponded with Frank. After her mother died on October 3, 1901, Emma married him at the Fairmount home of Reverend M. K. Hollister, thereby gaining access to a culture accessible to her only as the wife of a mountain man.

Initially she and Frank lived in the vacant Bell house on Anderson Pike, which Emma’s mother had left to her in a penciled will. On September 8, 1902 twin daughters Jean and Judith were delivered by Frank’s mother, Cynthia Jane Winchester Miles. But on July 1, 1903, B. F. Bell usurped Emma’s claim to the house and sold it to Francis Martin. Frank, Emma, and the twins spent the rest of the summer in canvas tents pitched in the yard of Frank’s sister and brother-in-law, Ab and Laura Hatfield, on Wilson Road in Summertown.

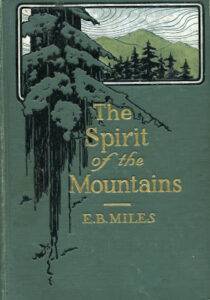

That summer Emma met sisters Alice MacGowan and Grace MacGowan Cooke, successful writers who helped Emma publish several of her poems in Harper’s Monthly. After giving birth to a son, Joe Winchester Miles, on February 1, 1905, Emma continued writing poems published in Century, Lippincott’s, and Harper’s that summer. She was also hard at work on her book The Spirit of the Mountains, published in October of 1905 by James Pott & Company of New York. She illustrated her landmark study of the way of life of mountain people living on Walden’s Ridge with photographs of Frank and his relatives. Emma explained how mountain people loved the wildness of their surroundings, calling upon them to unite against the corruption of civilization, represented by the summer employers who destroyed their self-sufficiency.

Emma herself sold sketches and post cards to the summer people, as she explained in a letter to Anna Ricketson of New Bedford, MA, soon after the birth of her fourth child, Katharine, called “Kitty”, on January 19, 1907. That summer they walked down the dusty road past the Bates place to make blackberry camp at the Reuben Brown cabin. In the fall of 1908 they moved to the Hedges house on the road to Signal Point where they gave a party on September 8 to celebrate the 6th birthday of Jean and Judith. Dancers ranged from big George Levi who “danced all over” to young Barney Miles in his work clothes, dancing with the graying Mrs. Catlow. After enjoying a basket of large ripe apples, they all joined in a rousing Virginia Reel.

That fall they picnicked at the Nelson Spring off Miles Road among hickories Emma described as “masses of crumpled shattered gold, with bits of sky let in like polished sapphires.” She was enthralled by the beauty of this mountaintop that had been lifted out of the valley “safe and still as an enchanted isle.” “The rest of the world fades to a dream,” she wrote; “its sounds reach you echo-thin and sweet, its lights are a necklace of jewels on the dusky velvet-bosom of the hills—all fairy like, unreal and dim.” In March of 1909 Emma bore another child, Mark.

At Sarah Key Patten’s house party at “Topside” in April of 1911, Emma painted a study of a pink moccasin flower one of the guests had found at Mabbitt Springs, and took orders for copies. In May she went sketching at the Davidson Place on the brow and with the children climbed down the bluff to the shelter of a rock house. In January, 1913 she was devastated by the death of her young son Mark. But in April she painted “Emma Bell Miles, Sketch Classes” on the drop leaf of her old sewing machine and nailed the sign to a tree on the Signal Point Road. She hoped to earn enough to move to town where she could find more work.

Emma and Kitty were hunting greens for poke salad when they met up with Judge and Mrs. Nathan Bachman and their little daughter Martha, dressed in a cowgirl outfit and halfway up a tree. The Bachmans asked Emma to do a painting of their summer house nestled in the blossoming orchard. She went to work immediately and was well pleased with the painting, as were the Bachmans who paid her $10 (this painting is now in the Walden Town Hall). Mrs. Bachman and Mrs. Lyle enrolled Martha and two Lyle children in Emma’s sketch class. On the way to visit her sister-in-law Laura Hatfield in Summertown, she stopped to see Mrs. Poindexter, who interrupted feeding her ducks and White Orphington chickens to pay Emma $5 for handmade books of her poems.

In early May Emma, Frank, the children took a picnic to the Nelson Spring and afterwards went for a walk in the woods with Frank’s brother, Joe Miles, and his family, who lived on Miles Road. Joe Miles was later famed for the quality of his whiskey and during Prohibition regularly dispatched his product, marked as “books,” via Railway Express to Judge Bachman when he was serving as a U. S. Senator in Washington, D. C.

In early May Emma, Frank, the children took a picnic to the Nelson Spring and afterwards went for a walk in the woods with Frank’s brother, Joe Miles, and his family, who lived on Miles Road. Joe Miles was later famed for the quality of his whiskey and during Prohibition regularly dispatched his product, marked as “books,” via Railway Express to Judge Bachman when he was serving as a U. S. Senator in Washington, D. C.

The center of the community was the store, post office, and dance pavilion at Albion View. Jo Andrews built the store and later sold it to Willowby Adams. James Alfred Conner was the postmaster for the post office moved there from Fairmount in 1893. “Every day around noon we would either drive the 2-1/2 miles or ride horseback over to the Top, take a mail bag and get the one we had left the day before with mail in it,” Sarah Key Patten of “Topside” recalled. “It was fun and you saw lots of people over there and generally bought a nickel’s worth of candy or maybe a bottle of soda pop.”

Under the management of A. W. Freudenberg and later of Lon Keef, the dance pavilion became a gathering place on Wednesday and Saturday nights for mountain people, summer colonists, and townspeople. Emma and her family attended a dance there in July of 1914. She described a rough lumber pavilion with four oil torches and a floor crowded with dancers, most native born. Over the counter of an enclosed stall at one end of the room, “Big Gus” Freudenberg was dispensing soda pop, ice cream cones, and sandwiches of split boiled weinerwurst. The three musicians were fiddler Jim Guess, a trusty from the county workhouse gang who played the guitar, and Dock Miles, Emma’s brother-in-law, on the banjo. After each set the men and boys paid 10 cents apiece, with $1.50 of the total collected during the evening going to each musician when they quit at midnight.

The next year the Albion View post office closed, and four years later Emma died in North Chattanooga on March 19, 1919. On July 4, 1924 the dances at the Albion View pavilion ended after a shoot out between rival bootleggers. But the sense of community that Albion View represented has enjoyed a modern day reincarnation here at the McCoy Farm & Gardens, where everyone is invited to attend the annual Memorial Day celebration on Monday, May 29, 2017. There’ll be plenty to eat, family activities, and good music–but no shoot out!